Culture

What is Christian Fundamentalism? A brief overview, and how to respond in love

As a church, we talk a lot about transforming culture. But to transform something, we first have to understand it.

•

This article is a written version of a talk I did recently on the topic. Since it’s such an important part of the transforming culture conversation rooted in our mission statement, I wanted to publish it here as a point of reference.

If you’ve spent any time reading the news, or social media for that matter (pretty sure I got all of us there), you have probably come across the word fundamentalism. It’s a growing force in the global ideological landscape. Yet it also hits close to home for us—without pointing fingers, fundamentalism has a strong presence here in Toowoomba.

Before launching in, let me provide just a few framing thoughts:

- This article isn’t designed to be an attack on anyone, rather, it’s naming a strong cultural undercurrent that needs to be called out.

- The message isn’t ‘fundamentalists are bad’. Fundamentalism isn’t so much a label for “those people” as it is a way of thinking that any of us can slip into.

- My hope is that in naming the problem, we can choose a better way. Most of us probably know people enmeshed in this way of thinking. My prayer is this article will give you some tools to help engage with them, and protect your own hearts and minds in a difficult cultural moment.

We’ll start by forming an understanding of the concept, then address the better alternative which Jesus gives us: discipleship.

What fundamentalism isn’t

In order to understand fundamentalism as a way of thinking, it’s important to first distinguish it from two other ideas that are connected, but definitely different:

Fundamentalism is not conservatism.

Conservatism is a valid worldview—one that, on its best day, values tradition, stability, and the preservation of what’s good. It often overlaps with fundamentalism, but they’re not the same thing. You can be a conservative without being a fundamentalist. And for that matter, you can be a fundamentalist Christian, Muslim, atheist, secularist, nationalist, or just about any kind of ‘ist’.

Fundamentalism is not orthodoxy.

Orthodoxy simply means holding to the historic teachings of Jesus and the Bible. Fundamentalism might look similar on the surface—“commitment to the fundamentals”—but it’s really a selective orthodoxy. Truth with the nuance ironed out.

It’s important to remember that the most dangerous lies are the ones that are mostly true. Fundamentalism latches onto good ideas but squeezes the life and mystery out of them.

Where does fundamentalism come from?

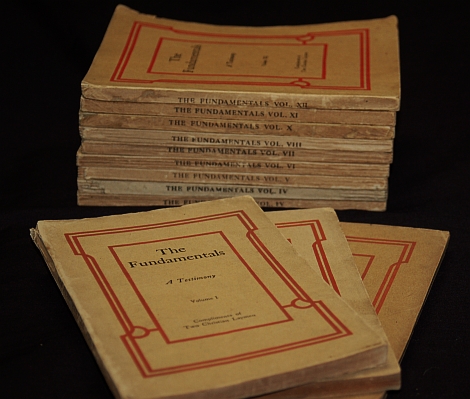

The word “fundamentalist” first appeared in the early 1900s. Between 1910 and 1915, a series of pamphlets called The Fundamentals were distributed across the United States, defending what the authors saw as the core truths of Christianity. They were a reaction against the rise of modernism and biblical critical scholarship. To be upfront, I haven’t read the pamphlets, but from what I understand they were pretty well articulated—some heavy-hitting theologians and commentators providing a balanced, nuanced critique of these new ideas. These pamphlets were financed by some wealthy oil barons and distributed—free—to over three million people.

The problem originated less from the pamphlets themselves, and more from the reaction they elicited. A movement quickly sprang up that was marked by anti-intellectualism, scepticism of science, and aversion to modern culture.

By the 1980’s this way of thinking was firmly entrenched in parts of American Evangelicalism. In the late ’80’s and early ’90’s a group of scholars set out to study this phenomenon. They widened the definition to include fundamentalist tendencies in any worldview, not just Christianity. Our modern understanding of fundamentalism is rooted in this approach—it’s a corruption of any kind of worldview, not just American Evangelical Christianity.

Fundamentalism: A narrative

Rather than thinking of fundamentalism as a coherent ideology, it’s probably better understood as an overarching narrative that shapes one’s worldview. If you survey the literature, there isn’t one agreed-upon definition of fundamentalism. What you get instead is a series of features that, put together, shape this narrative. Here are five that come up regularly:

- Rigid authority. In Christian fundamentalism, authority usually centres on the Bible. The issue isn’t believing the Bible is authoritative (we do too); it’s believing our interpretation is the only valid one. There’s no room for nuance, discussion, or mystery. The Bible becomes a rulebook rather than a living story that invites wrestling and growth.

- Boundary making. Fundamentalism thrives on clear boundaries: who’s in, who’s out, who’s right, who’s wrong. Certain cultural issues—sexuality, abortion, political allegiance, etc—become tests of “true Christianity.” The problem isn’t caring about these issues; it’s using them to draw lines between people.

- In- and out-groups: When boundary-making hardens, you get a strong us and them mindset: Those who are “true to the faith” versus those who have “compromised with the world.” This thinking fractures community and breeds suspicion rather than love.

- The cosmic war: Fundamentalism often imagines life as a grand cosmic battle between the pure and the corrupt. Now, Scripture does speak of spiritual conflict—the Kingdom of God opposing the powers of darkness (e.g. Ephesians 6:12). But in fundamentalism, the “enemy” isn’t sin or evil; it’s people and culture itself. The result is paranoia, conspiracy thinking, and fear.

- Selective traditionalism: Fundamentalists see themselves as the guardians of “true faith,” but often their beliefs are more modern than ancient—things like strict biblical literalism, family values tied to 1950s culture, or the Protestant work ethic. These aren’t bad in and of themselves (well, maybe strict biblical literalism is), but they’re not the historic centre of Christianity. The irony is that fundamentalism claims to be traditional while ignoring much of church history.

Jesus said we would know a tree by its fruit (Matthew 7:16). So what fruit does this kind of faith produce?

- Fear rather than love

- Certainty rather than trust

- Suspicion of outsiders

- Protection of harmful ideas or practices (like control or coercion)

- In its extreme forms, even violence or neglect done “in God’s name”

The result is often cultural isolation and a distorted picture of the gospel.

The alternative: discipleship

If we stop there, the message is simply “fundamentalism is bad.” But Scripture gives us a much better invitation.

The opposite of fundamentalism isn’t progressivism—it’s discipleship. Rather than defining ourselves by what we reject, discipleship calls us to follow Jesus directly and be transformed by Him.

You can actually map the heart of a disciple along those same five pillars:

| Fundamentalism | Discipleship |

|---|---|

| Rigid authority | Growth mindset |

| Boundary making | Boundary breaking |

| In/out groups | Centered set |

| Cosmic war | Love for the world |

| Selective traditionalism | The way of Jesus |

Let’s unpack those briefly.

- Growth mindset (instead of rigid authority): Scripture isn’t a static rulebook but a story to be wrestled with. The Bible is authoritative, but our interpretation isn’t. There’s always more to learn — and that posture of humility is what allows the Spirit to transform us.

- Boundary breaking (instead of boundary making): Jesus constantly crossed social and religious boundaries—eating with tax collectors, touching lepers, and speaking with a Samaritan woman (John 4). The early church wrestled with this too, as Gentiles were welcomed into God’s family. The way of Jesus opens doors rather than guarding gates.

- Centered set (instead of in/out groups): Rather than deciding who’s “in” or “out,” discipleship is about direction—a diverse group of people moving toward Jesus together. This “centred set” approach (a core Vineyard idea) reminds us that the church’s unity comes from who we’re following, not how perfectly we agree.

- Love for the world (instead of cosmic war): The world isn’t the enemy. Sin, death, and the devil are. When we see people as enemies to best rather than neighbours to love, we lose sight of the gospel.

- The way of Jesus (instead of selective traditionalism): Jesus invites us to take His yoke upon us and learn from Him (Matthew 11:29). Discipleship isn’t about preserving a cultural moment or moral code; it’s about becoming like Christ. It’s an ancient way to live faithfully in a chaotic modern world.

Our Response

So what do we do with fundamentalism—in ourselves, and in others?

Let’s start with what not to do. Whatever you do, don’t criticise, belittle, or hate on people you might see as steeped in fundamentalist thinking. This includes people on the internet. That’s just contributing to the problem. Don’t pull away from them either—I have personally tried to shift my thinking so that in my mind they aren’t bad people, but victims of fear in a crazy, social-media-echo-chamber world. More on that in a moment.

At the same time, don’t compromise your beliefs out of fear of becoming fundamentalist. Fear shouldn’t be the driver of anything in a Christian worldview—it should be love. Hold on to your convictions, while remaining open to different ideas or interpretation.

Instead, begin by examining your own heart. Remember that weird saying of Jesus about the log in your eye and the speck in your brother’s (Matthew 7:3-5)? This one applies here. Fundamentalism is a way of thinking that can creep in for all of us. Ask yourself whether fear is driving any of the beliefs we discussed above.

When you’ve done that, you have the opportunity to be a non-anxious presence in the lives of those wrapped in fear and control. There’s a beautiful quote by Richard Rohr I keep coming back to:

When we commit ourselves to living gently and lovingly in the way of Jesus, we hold a light to the fear-driven worldview that fundamentalism cultivates. When we approach fundamentalists with love and compassion—not trying to argue our point of view—we undermine the us-and-them narratives that drive them.

A practice

One of Jesus’ wildest teachings comes from the sermon on the mount, where he says:

“Love your enemies, bless those who curse you, do good to those who hate you, and pray for those who spitefully use you and persecute you” — Matthew 5:44

What if—right now—you took a moment to think about the people you might consider your ‘enemies’, and genuinely pray for their blessing. Not a ‘help them see the error of their ways’ prayer. Generous prayer for their wellbeing.

At the very least, this exercise will help guard your heart against the entrapment of fundamentalism. Who knows, God may even answer your prayers. He is in the habit of doing that.

Did you find this article helpful? How did you go with the practice? I’d love to hear your thoughts, feel free to drop a comment using the form below.

Cover image credit: Eyasu Etsub via Unsplash

2 responses to “What is Christian Fundamentalism? A brief overview, and how to respond in love”

-

I understand your comments in part. Yes, love people who are different to us but there does remain the challenge given the evil in the world. Do we allow or vote for evil to continue? Surely not. If we have the power to do so we make a stand. A fundamentalist would more likely take a stand for faith against evil. It is called conviction. Therefore there is a place for some fundamental approaches.

-

Hey Ruth,

Thanks for your comment, I appreciate you raising a crucial point! You’ve caught onto a tension we have to walk as followers of Jesus. On one hand we do need to love those we disagree with, even on important points. On the other—in the prophetic tradition—we are encouraged to rally against evil in the world. Sometimes we can do both, but other times we have to choose our battles… this is a steep learning curve for me personally 😌

However, I don’t agree that fundamentalists are inherently more likely to stand against evil. We can see both historically and in the present day that the driving force behind fundamentalism is fear. The result is a kind of activism that sees the world as the enemy, rather than those Jesus died on the cross for. Love was Jesus’ motivation and it should be ours also. There is a beautiful tradition of activism in the church rooted in love rather than fear.

Curious to hear your thoughts!

Chris

-

More posts

2026: The year of experiments

What does it look like to live out our Matthew 11:28-30 vision in 2026? We’re glad you asked…

A prayer for our enemies

In an increasingly divided world, praying for our enemies is a profound act of resistance. Here’s a helpful framework.

All about kids church at TVC

At Toowoomba Vineyard Church we have a heart for our littlies and want them to enjoy the teachings and fellowship of church just as…

How to connect

Are you looking for a church to call home? Want to learn more about Jesus or Christianity? We’d love to connect. You can get in touch at the link below, or visit us on Sunday.

Leave a Reply